L’autostima si impara con la legge dei cento passi della mediazione

Genitori ed insegnanti si chiedono spesso come poter aiutare lo sviluppo dell’autostima nei propri figli e alunni. Ad AIS – Assisi International School, la scuola di Fondazione Patrizio Paoletti basata su Metodo Montessori e Pedagogia per il Terzo MillennioPedagogia per il Terzo Millennio (PTM) è un metodo interdis... Leggi, gli alunni possono sviluppare l’autostima attraverso il lavoro personalizzato sull’autonomia. Imparare a muoversi con sicurezza e naturalezza nel proprio ambiente, sapendo prendersi cura di se stessi e degli altri, rende ogni bambino sicuro e sereno. La fiduciaLa fiducia, un'emozione cruciale nel tessuto delle relazioni... Leggi e la tranquillità sono, infatti, alla base dell’autostima.

Metodologicamente, si tratta di applicare la corretta distanza tra maggiore e minore in azioni molto semplici, per mezzo di costanza e pazienzaLa pazienza, sia come emozione che come virtù, si manifesta... Leggi. I compiti più efficaci sono quelli quotidiani come provare e riuscire a mettersi le scarpe, piegare e appendere un indumento, riordinare dopo aver lavorato, comporre una parola con le lettere mobili, ordinare in base ad alcune caratteristiche… dà ad ogni bambino, fin dai primi anni di vita, una grande fiducia nelle proprie capacità, nella possibilità di apprendere e migliorare ogni giorno, a patto che l’educatore si mantenga alla giusta distanza.

Ad una prima lettura, il fatto che la Mediazione preveda una distanza nella relazione educativa può suonare strano: non abbiamo l’idea di dover essere con l’educando, al suo fianco? Sì è vero, l’educatore ha il dovere di essere sempre presente col suo sguardo vigile nei confronti dell’educando e di accompagnarlo nelle tappe della sua evoluzione, ma questo non deve significare sostituirsi nell’affrontare gli ostacoli. Gli ostacoli sono, infatti, un allenamento insostituibile per ogni essere umano, a patto che siano commisurati alle capacità che l’educando effettivamente può mettere in campo nel momento presente. È qui che entra in giocoIl gioco non è solo un'attività di svago, ma un elemento f... Leggi il ruolo dell’educatore in quanto mediatore, il suo compito è aiutare il minore ad affrontare l’ostacolo ancora troppo grande per lui. Non si tratta di eliminare l’ostacolo, ma di fare in modo che, attraverso il ‘confronto mediato’, il minore possa fare il passo successivo del percorso, quel passo che realizza il suo attuale possibile avanzamento.

La legge dei cento passi

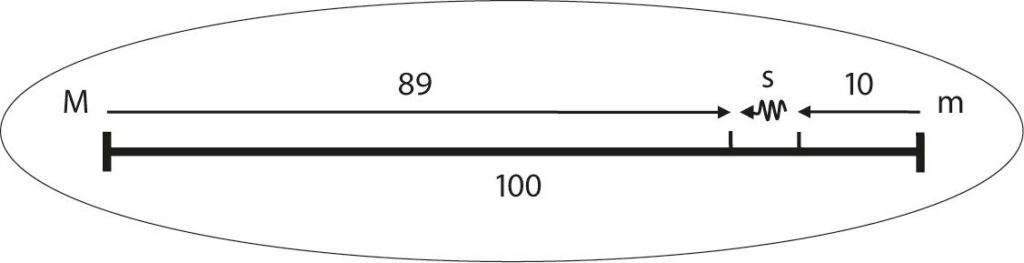

In PedagogiaLa pedagogia rappresenta un ponte tra le diverse discipline ... Leggi per il Terzo Millennio (PTM) il processo in continuo divenire della mediazione viene caratterizzato come “legge dei cento passi”, ovvero se immaginiamo di dividere la distanza che separa il maggiore dal minore in 100 parti, e il minore è capace di compiere al momento solo 10 passi, il maggiore si avvicinerà a lui di 89 passi. In questo modo il minore sentirà il desiderio di raggiungere il maggiore, trovando la spinta per compiere quel passo in più che ancora li separa. Tale sforzo che attesta l’avvenuta crescita e apprendimentoIl termine apprendimento - con i sinonimi imparare, assimila... Leggi del minore viene chiamato ‘supersforzo’, ed è necessario al suo avanzamento.

Nello schema qui presentato il ‘supersforzo’ che il maggiore chiede al minore per crescere è rappresentato dalla freccia ondulata ‘s’.

L’undicesimo passo della nostra metafora non rappresenta per il minore un semplice sforzo, cioè l’utilizzo delle capacità già acquisite, ma è un ‘supersforzo’ in quanto gli richiede di sviluppare nuove capacità, nuova comprensione, nuova visione, rispetto alle capacità già acquisite. Senza ‘supersforzi’, come è noto a tutti gli educatori, non c’è progresso. L’abilità del mediatore sta nell’individuare quella che Vygotskij chiama Zona di Sviluppo Prossimale. Il processo della mediazione consente al maggiore di posizionarsi adeguatamente e fare in modo che il minore sviluppi il risultato significativo che al momento presente può effettivamente perseguire.

AUTOSTIMA Come promuoverla

Compila il form

"*" indica i campi obbligatori

in classe e in famiglia

e guarda subito il webinar

A scuola

E a scuola? Gli insegnanti sanno quanto per un alunno incontrare una difficoltà troppo grande può essere demotivante e non stimola il desiderio di imparare. D’altro canto, non avere un nuovo avanzamento da fare, attraverso uno sforzo, può portare a noiaDefinizione neuroscientifica e psicologica La noia è un'emo... Leggi e demotivazione. Calibrando le richieste grazie alla capacità di mediazione, al saper trovare il momento e lo stimolo che possano far acquisire un nuovo avanzamento, e dando spazi agli alunni per poter scegliere modalità e attività da svolgere, anche a scuola si può aiutare lo sviluppo dell’autostima sottolineando e celebrando ogni risultato ottenuto. In quest’ottica l’errore è sempre accolto come un ‘maestro’ perché evidenzia le aree su cui ogni insegnante e studente deve concentrare la propria attenzioneL'attenzione è un processo cognitivo complesso e multidimen... Leggi, per superarlo.

In PTM, perché il processo di supporto detto ‘scaffolding’ abbia effetto, l’azione di sostegno prevista richiede che il maggiore espleti alcune specifiche funzioni, quali:

- Sostenere l’allievo e motivarlo soprattutto nei momenti di difficoltà;

- Vigilare sul livello di difficoltà dei compiti proposti all’allievo stesso perché siano adeguati alle sue capacità del momento;

- Sollecitare l’allievo fino al raggiungimento dell’obiettivo;

- Sottolineare all’allievo stesso gli aspetti fondanti del compito che va svolgendo;

- Aiutarlo a gestire la frustrazioneLa frustrazione, dal punto di vista neuroscientifico e psico... Leggi;

- Mostrare come può essere svolto il compito ponendosi da modello.

Il sostegno offerto dal maggiore consente all’allievo di fare proprio il sapere, divenendo cosciente dei risultati conseguiti. Accorgersi dei traguardi ottenuti e acquisire la consapevolezza di possedere le competenze necessarie per svolgere i compiti richiesti nutre il discente ad aumentare e stabilizzare la propria autostima.

Maria Montessori insegnava che ogni allievo chiede all’adulto: ‘aiutami a fare da solo’. Quando un bambino impara, grazie al corretto aiuto dell’adulto, a fare in autonomia una cosa per cui prima aveva bisogno di aiuto, allora il suo viso si illumina e lui sa che tutto quello che ora non riesce a fare è alla sua portata grazie all’aiuto che può ricevere per poi fare da solo. Così inizia il processo di sviluppo dell’autostima come fondata valorizzazione delle proprie capacità.

Sii parte del cambiamento. Condividere responsabilmente contenuti è un gesto che significa sostenibilità