The neuroscience of self-esteem: 5 research-based tips for valuing ourselves

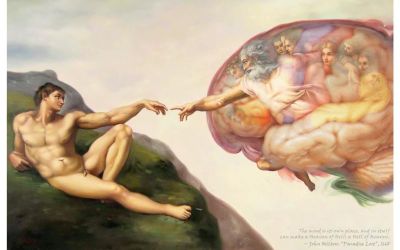

Although self-esteem is widely studied in the behavioral sciences, its neuroanatomical basis is still largely unknown. For example, reduced self-esteem has been associated with increased brain activity in regions of the anterior insula and dorsal part of the anterior cingulate cortex, the same regions that have been shown to be activated by experiences of social rejection and to be linked with self-discomfort.

These brain regions were observed by Naomi Eisenberg and colleagues, who hypothesized that a mechanism exists in the brain that they called ‘sociometer’, a mechanism that supposedly translates perceptions of rejection or acceptance by others into self-esteem. Their research showed that individuals may have different attitudes to social feedback, with more or less activity in the prefrontal cortexThe prefrontal cortex plays a fundamental role in numerous p... More, an area generally associated with self-referential processes. The difference in the processing of social feedback could be related to the concept of internal or external locus of control.

Preliminary results from another study by Dartmouth College show, in fact, that lasting self-esteem correlates with a greater white matterWhite matter is a part of the central nervous system made up... More connection between the frontal cortex and the ventral striatum, an area involved in the feeling of gratification and the so-called internal ‘locus of control’. We speak of an internal locus of control when a person ascribes power over events to themselves, as opposed to an external locus of control, that is, when one tends to delegate responsibility for what happens outside oneself.

In summary, we can say that, according to this research, self-esteem goes hand in hand with an increase in the volume of grey matter in the brain regions responsible for adaptive responses to events that generate stressWhat is stress? From a clinical perspective, stress is a phy... More and an increase in white matter in the areas that connect self-referential processes with gratification. From a psychological point of view, these changes in the brain appear to be correlated with attributing the ability to influence events in our lives to ourselves.

There is also a risk here, however, and attributing capabilities to ourselves can backfire. It is necessary to learn the art of mediation between the ideal self, the image of us which we tend to attribute maximum ability to, and the actual self that we experience every day. The mediation process can lead us to find that intermediate point where we come closer to our aspirations, without falling into frustration, but instead realizing concrete results that will form a solid foundation for our self-evaluation.

With this in mind, Moffit and colleagues found that the concept of self-compassion, intended as focusing on kindness, compassionCompassion is a positive emotion that arises when we not onl... More and understanding towards oneself, is more effective than simply focusing on one’s positive qualities, to improve, for example, dissatisfaction with one’s body.

Here, then, are 5 tips based on self-esteem research to apply to education:

- Practicing self-acceptance not in a passive or uncritical sense, but making gratitudeGratitude, a positive emotion linked to the recognition and ... More for life the basis of my self-evaluation. If I realize that the mere fact that life is betting on me is of enormous value, this will support me in my self-evaluation.

- Set achievable goals, thus allowing the brain to acquire solid ability benchmarks, which can be assessed on a measurement scale.

- Nurturing memories through active reflection. In order to evaluate, the brain makes reference to memories, but these are not fixed, they can be revisited and reappraised to contemplate events from new points of view.

- Cultivate positive relationships in which we highlight each other’s skills and value in a supportive manner, without fear of criticism

- Helping others when possible is not only a socially useful action, but also a self-confirmation of our value as being able to give.

Agroskin, D., Klackl, J., & Jonas, E. (2014). The self-liking brain: a VBM study on the structural substrate of self-esteem. PloS one, 9(1), e86430.

DeWall, C. N., MacDonald, G., Webster, G. D., Masten, C. L., Baumeister, R. F., Powell, C., … & Eisenberger, N. I. (2010). Acetaminophen reduces social pain: Behavioral and neural evidence. Psychological science, 21(7), 931-937.

Donnellan, M. B., Trzesniewski, K. H., & Robins, R. W. (2011). Self-esteem: Enduring issues and controversies.

Eisenberger, N. I., Lieberman, M. D., & Williams, K. D. (2003). Does rejection hurt? An fMRI study of social exclusion. Science, 302(5643), 290-292.

Eisenberger, N. I., Taylor, S. E., Gable, S. L., Hilmert, C. J., & Lieberman, M. D. (2007). Neural pathways link social support to attenuated neuroendocrine stress responses. Neuroimage, 35(4), 1601-1612.

Eisenberger, N. I., Inagaki, T. K., Muscatell, K. A., Byrne Haltom, K. E., & Leary, M. R. (2011). The neural sociometer: brain mechanisms underlying state self-esteem. Journal of cognitive neuroscience, 23(11), 3448-3455.

Erol, R. Y., & Orth, U. (2011). Self-esteem development from age 14 to 30 years: a longitudinal study. Journal of personality and social psychology, 101(3), 607.

James, W. (1890). The Principles Of Psychology Volume II By William James (1890).

Kross, E., Egner, T., Ochsner, K., Hirsch, J., & Downey, G. (2007). Neural dynamics of rejection sensitivity. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 19(6), 945-956.

MacDonald, G., & Leary, M. R. (2012). Individual differences in self-esteem.

Masten, C. L., Eisenberger, N. I., Borofsky, L. A., Pfeifer, J. H., McNealy, K., Mazziotta, J. C., & Dapretto, M. (2009). Neural correlates of social exclusion during adolescenceWhat is meant by adolescence? Adolescence is understood as t... More: understanding the distress of peer rejection. Social cognitive and affective neuroscience, 4(2), 143-157.

Meier, L. L., Orth, U., Denissen, J. J., & Kühnel, A. (2011). Age differences in instability, contingency, and level of self-esteem across the life span. Journal of Research in Personality, 45(6), 604-612.

Moffitt, R. L., Neumann, D. L., & Williamson, S. P. (2018). Comparing the efficacy of a brief self-esteem and self-compassion intervention for state body dissatisfaction and self-improvement motivationMotivation: a scientific perspective Motivation is a fundame... More. Body Image, 27, 67-76.

Onoda, K., Okamoto, Y., Nakashima, K. I., Nittono, H., Ura, M., & Yamawaki, S. (2009). Decreased ventral anterior cingulate cortex activity is associated with reduced social pain during emotional support. Social neuroscience, 4(5), 443-454.

Robins, R. W., Trzesniewski, K. H., Tracy, J. L., Gosling, S. D., & Potter, J. (2002). Global self-esteem across the life span. Psychology and aging, 17(3), 423.

Shaw, B. A., Liang, J., & Krause, N. (2010). Age and race differences in the trajectories of self-esteem. Psychology and Aging, 25(1), 84.

Wagner, J., Gerstorf, D., Hoppmann, C., & Luszcz, M. A. (2013). The nature and correlates of self-esteem trajectories in late life. Journal of personality and social psychology, 105(1), 139.

Be part of the change. Responsibly sharing content is an act of sustainability.

Let's train emotional intelligenceThe first definition of Emotional Intelligence as such was p... More: what emotion does this article arouse in you?